The 4th of May, is known in Holland as

Dodenherdenking, or

War Dead Remembrance. Similar to Israel's Memorial day followed by Independence day, the Dutch have a similar progression. The official, nationally televised commemoration begins in the evening with a service at

De Oude Kerk (the Old Church) in central Amsterdam, after which veterans and victims’ relatives lay wreaths at the National War Memorial on nearby

Dam square. Church bells ring for a quarter of an hour till 8 pm, when there is a nationwide two-minute silence. Dignitaries and other victims’ groups then lay more wreaths and a child reads out a self-written poem, selected by a local jury. A ceremonial procession past the National War Memorial marks the end of proceedings. As the saying in Holland goes, 'No celebration without commemoration'. This sentiment reflects gratitude, but it also a value placed on the progression of redemption.

We constantly evoke World War II, and the Holocaust with a pledge to prevent further bloodshed. We're not doing so well. I believe that precisely at this fault-line between the fleeting historical awareness of the event, and our collective memory, these rituals may bridge that gap by offering the opportunity for us to experience the redemptive process on an individual, national, and universal level.

When John Donne

preached to his congregants, he chose to appeal to them through what he called 'the gallery of the soul'; memory:Of our perverseness in both faculties, understanding, and will, God may complain, but as much of our memory: for, for the rectifying of the will, the understanding must be rectified; and that implies great difficulty: But the memory is so familiar, and so present, and so ready a faculty, as will always answer, if we but speak to it, and aske it, what God hath done for us, or for others. The art of salvation, is but the art of memory.

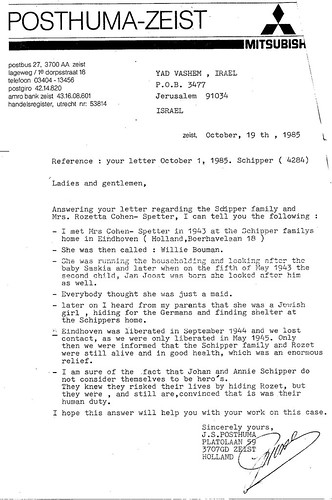

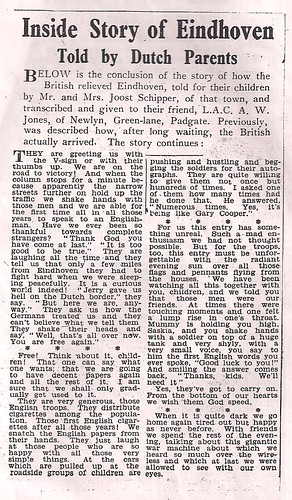

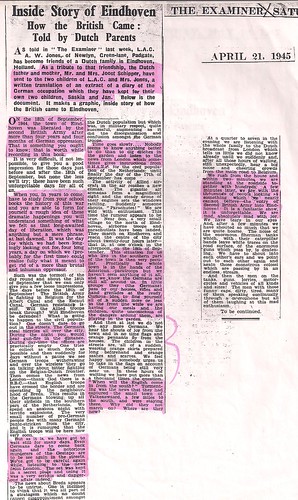

In preparation for liberation day, and in honour of remembrance day, the following are extracts from a memoir which was published in the English paper The Examiner in April of 1945. The diary was written by JHT Schipper (my grandfather) for his two children Saskia and Jan. Schipper translated these extracts for John and Maureen Jones, the children of Alfred Wynn Jones, a member of the Balloon Barrage who was stationed in Eindhoven, as an expression of the friendship that developed between them. Sentences in orange are my own.

On the 18th of September, 1944, the town of Eindhoven was liberated by the second British Army after more than four years and four months of German oppression. That is something you ought to know; that is worth while recording in this book […] When you, in years to come, have to study from your school books the history of this war and you are able to form for yourself a rough idea of these dramatic happenings you will understand something of what we felt as that long-awaited day of liberation, which was anything but a mere phase, at last dawned. It was the day for which we had been longingly looking out for four long years, a day on which we (probably for the first time,) could realise fully what it means to get rid of a more than brutal and inhuman oppressor […]

One doesn't dare to go out in the streets. The Germans steal bicycles all over the city. During the night, you would hear gun-fire in the distance. During day-time the offices are practically empty. One tries to collect as much food as possible and then suddenly without pause we see German troops withdrawing and over the wireless they go on talking about the bitter fighting on the Belgian-Dutch frontier.

After the Germans and Dutch Nazis flee the town, it seems as if the English will arrive shortly

But as it is, we have got to wait still for many days. Even Germans dare to come back again, and the notorious murderers of the Gestapo are to be seen again in the streets. We’ve got to be careful again while listening to the news from London. The set was kept in a secret place and using it was a very serious and dangerous affair indeed [...]

Time goes slowly…Nobody seems to know anything better to do than to dig ditches in the garden and listen to the news from London…

After witnessing numerous air battles, news arrives that paratroopers have landed at Son (a small village north of Eindhoven) and have marched to the centre of Eindhoven.

This situation for us who live in the southern part of the town is then very peculiar. Practically the whole town is in the hands of the American paratroopers but we haven’t seen anything of it at all, and we know the Germans are still all around us. In little groups they (the Germans) pass by our houses, rifles and hand grenades at the ready. Curious idea to find yourself all of a sudden more or less in the front line while we are having our meals and the children, quite unconscious of the dangers around them, are playing in the garden.

People in the town are euphoric and celebrating liberation; it turns out to be premature. The Schippers are warned to take their flags in for the Germans are still quite near.

In these hours of waiting we have put more than a thousand times the question, 'When will the English come in from the south?' Tormenting was the news that they had captured the small town of Valkenswaard, a few miles to the south and were staying there. Why did they not march on? Where are they now?

The Israel Museum just underwent a $100 million renovation. One of the highlights of the visit i took with my mum was the Tzedek VeShalom Synagogue, built in 1734 in Paramaribo, Suriname. For the woodworkers out there, the ark is made of Cyprus wood and mahogany. Below is a video about the synagogue and some really cool footage of the restoration. Just some brief history of the settlement of Jews in the area. According to our tour guide, in 1630, about 500 Jews came to Suriname to establish sugar plantations. They named them after cities in the land of Israel: Hebron, Tiberias, Jerusalem, Beersheba, to name a few of the plantations that existed in Suriname. The name of the Jewish settlement was actually the Jodensavanne, or the Jewish Savannah. To read more about the Jewish community in Suriname, click here.

The Israel Museum just underwent a $100 million renovation. One of the highlights of the visit i took with my mum was the Tzedek VeShalom Synagogue, built in 1734 in Paramaribo, Suriname. For the woodworkers out there, the ark is made of Cyprus wood and mahogany. Below is a video about the synagogue and some really cool footage of the restoration. Just some brief history of the settlement of Jews in the area. According to our tour guide, in 1630, about 500 Jews came to Suriname to establish sugar plantations. They named them after cities in the land of Israel: Hebron, Tiberias, Jerusalem, Beersheba, to name a few of the plantations that existed in Suriname. The name of the Jewish settlement was actually the Jodensavanne, or the Jewish Savannah. To read more about the Jewish community in Suriname, click here.

In addition to paying homage to their biblical roots, the Jews of Suriname paid tribute to their Spanish-Portugese Dutch roots. Whilst having a peek around the synagogue, we noticed that one of the finials for the Torah scrolls was an unmistakable nod to the Westerkerk in Amsterdam. You know--the one that Anne Frank mentions? Pretty cool, eh? How many synagogues today would commission, let alone tolerate, a Torah adornment in the style of a church? Pretty remarkable...

In addition to paying homage to their biblical roots, the Jews of Suriname paid tribute to their Spanish-Portugese Dutch roots. Whilst having a peek around the synagogue, we noticed that one of the finials for the Torah scrolls was an unmistakable nod to the Westerkerk in Amsterdam. You know--the one that Anne Frank mentions? Pretty cool, eh? How many synagogues today would commission, let alone tolerate, a Torah adornment in the style of a church? Pretty remarkable...