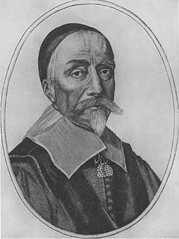

In the past, we have noted the parallel developments in biblical scholarship and politics in the Netherlands and England (link), specifically the Authorised Version and the Statenvertaling. We have also noted the influence of Hugo De Groot (Grotius) on John Milton. Recently, i came across a poem by Jakob Reefsen (Jacobus Revius), a Hebrew scholar who worked on the Statenvertaling and who also composed religious as well as secular poetry. It reminded me of a poem by Donne, and, when taken together, there are some similarities, but overall, Revius' seems like a lesson in how not to write poetry. But i'll let you decide for yourself:

In the past, we have noted the parallel developments in biblical scholarship and politics in the Netherlands and England (link), specifically the Authorised Version and the Statenvertaling. We have also noted the influence of Hugo De Groot (Grotius) on John Milton. Recently, i came across a poem by Jakob Reefsen (Jacobus Revius), a Hebrew scholar who worked on the Statenvertaling and who also composed religious as well as secular poetry. It reminded me of a poem by Donne, and, when taken together, there are some similarities, but overall, Revius' seems like a lesson in how not to write poetry. But i'll let you decide for yourself:

'Hy Droegh Onse Smerten' (1630 in Over-Ysselsche Sangen en Dichten)

T'en sijn de Joden niet, Heer Jesu, die u cruysten,

Noch die verradelijck u togen voort gericht,

Noch die versmadelijck u spogen int gesicht,

Noch die u knevelden, en stieten u vol puysten,T'en sijn de crijghs-luy niet die met haer felle vuysten

Den rietstock hebben of den hamer opgelicht,

Of het vervloecte hout op Golgotha gesticht,

Of over uwen rock tsaem dobbelden en tuyschten:Ick bent, ô Heer, ick bent die u dit hebt gedaen,

Ick ben den swaren boom die u had overlaen,

Ick ben de taeye streng daermee ghy ginct gebonden,De nagel, en de speer, de geessel die u sloech,

De bloet-bedropen croon die uwen schedel droech:

Want dit is al geschiet, eylaes! om mijne sonden.

In English ( i grabbed the translation here):

He carried our sorrows. It is not the Jews

alone, Lord Jesus, that had you crucified;

betraying you, dragging you to the court,

hating your guts, spitting in your face,

binding you, tattooing you with bruises.

Nor only the soldiers

who with their ready fists

raised the reed, lifted the hammer high,

fixed the cursed wood at the place of the skull

and squabbled, dicing for your coat.

It's me, my God, me who did this to you.

I am the heavy tree that bore you down,

the cord that cut you mercilessly. Me.

The nail and spear. The whip they slashed you with.

The crown of blood you wore upon your brow.

Oh, all this happened on account of my own sin.

And here is of course Donne's Holy Sonnet XI (written 1609-1611?):

Spit in my face, you Jews, and pierce my side,

Buffet, and scoff, scourge, and crucify me,

For I have sinn'd, and sinne', and only He,

Who could do no iniquity, hath died.

But by my death can not be satisfied

My sins, which pass the Jews' impiety.

They kill'd once an inglorious man, but I

Crucify him daily, being now glorified.

O let me then His strange love still admire ;

Kings pardon, but He bore our punishment ;

And Jacob came clothed in vile harsh attire,

But to supplant, and with gainful intent ;

God clothed Himself in vile man's flesh, that so

He might be weak enough to suffer woe.