De Stijl has been capturing my imagination for quite some time now. But it wasn't until fairly recently that i have been able to contextualise it. After the first world war, there were two main avant-garde Dutch movements in architecture and decorative arts. There was The Amsterdam School and De Stijl, also known as Neo-Plasticism. Both were related to Art Nouveau, the Arts and Crafts, and German Expressionism. They were into a unified style, and definitely subscribed to Morris's idea that art could change society. But that is about where these two movements go their own ways. As Alan Colquhoun explains it,

De Stijl has been capturing my imagination for quite some time now. But it wasn't until fairly recently that i have been able to contextualise it. After the first world war, there were two main avant-garde Dutch movements in architecture and decorative arts. There was The Amsterdam School and De Stijl, also known as Neo-Plasticism. Both were related to Art Nouveau, the Arts and Crafts, and German Expressionism. They were into a unified style, and definitely subscribed to Morris's idea that art could change society. But that is about where these two movements go their own ways. As Alan Colquhoun explains it,Each inherited a different strand of the earlier movements--the vitalistic, individualistic strand in the case of the Amsterdam School and the rationalist, impersonal strand in the case of De Stijl. Each movement condemned the other, ignoring their shared aims and origins. (Modern Architecture, Oxford History of Art)

Jammer. Hopefully we'll come back to the A'dam School, but just some short background on them: Michel de Klerk (1884-1923) would be the main name to associate with the movement. They were into taking traditional architecture and tweaking it into fantastical, weird design, and they held dear the craftsman relationship to materials. Personally, of the two, the A'dam school's ethos is more to my liking, but i think De Stijl has loads to offer. So let's get back to them!

Jammer. Hopefully we'll come back to the A'dam School, but just some short background on them: Michel de Klerk (1884-1923) would be the main name to associate with the movement. They were into taking traditional architecture and tweaking it into fantastical, weird design, and they held dear the craftsman relationship to materials. Personally, of the two, the A'dam school's ethos is more to my liking, but i think De Stijl has loads to offer. So let's get back to them!Theo van Doesburg (1883-1931)

Piet Mondrian (1872-1944)--some of my friends had no idea he was Dutch based on his surname. It was originally Mondriaan, but he omitted the second 'a' to make himself sound less Dutch. Mission accomplished, i guess.

Gerrit Rietveld (1888-1964)

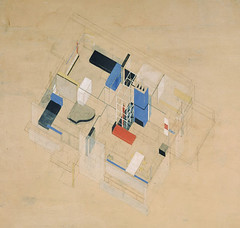

In 1924, Van Doesburg published the manifesto of De Stijl in the eponymously named magazine he founded with Mondrian and other artists of the movement in 1917. You can read it here. De Stijl rejected craftsmanship, favouring geometrical anti-naturalism, and, according to some, was a misinterpretation and an extreme form of the abstraction of Cubism. But what was up with all the abstraction? Could they just not paint or draw? What were they getting at? Basically, according to Carsten-Peter Warncke, Mondrian, Vantongerloo, van Doesburg, and Huszar were all trying to get back to the basic principles of art; colours, shapes, planes, and lines. They wished to create a metaphorical language, and create an ideal world counter to reality, transcending language barriers. You can see Neo-Platonism's influence on Mondrian's obsession with the purity of art and spirit, and its aim for the absolute. Style was a manifestation of a particular age's attempt to express the absolute. Therefore, Mondrian felt that the best possible style was one in which 'the individual was most strongly subjected to the universal.'

Indeed the contradiction inherent in the movement is summed up by Mondrian himself:

The universal in style must be expressed by the individual, i.e. the way in which style is formed

It remains remarkable that Mondrian should have succeeded in combining the disparate parts of the painting in such a harmonious structure. Again, he could only have achieved this through the multifaceted ambiguity that pervades the various elements of the painting. [...] a perfect harmony of opposites [...] Nothing is fixed in this system , except for the basic elements and the aim of balancing the different forces. This presupposes that all our seemingly secure assumptions should be questioned again and again. (Warncke, p.20)And, in explaining the differences between Mondrian and van Doesburg, we are surely reminded of different poetic schools of thought:

Mondrian's construction of squares and lines is a process that leads to harmony and rest to the extent that we forget everything that might be reminiscent of processes, while van Doesburg's pictures show a completely different approach to dynamics, with colour squares that border on each other harshly and are right next to each other. This dynamic has the rank of an elementary force which can only be tamed with great difficulty and changed in such a way that the well-balanced painting oscillates in its visual impact, paradoxically demonstrating harmony as vibrating restfulness. (Warncke, p.26)Milton and Donne, anyone?

Jakob van Domselaer was the only musician associated with the movement. Here you can listen to his Proeven van Stijlkunst, inspired by Mondrian's paintings

Dada to Pop--cool essay

Artlex Entry on De Stijl

To read De Stijl magazine, click here

Interesting article (or MA thesis) by Runette Kruger about the integrative tendency of the movement, unparalleled in Modern art, in which the artists of De Stijl equally evoked the technological as well as the transcendent as indicators of humanity's spiritual and cultural progress

James Presley-- Mondrian van Doesburg